US Customs and Border Patrol agents flew unmanned aerial vehicles over crowds of Black Lives Matter protesters in at least 15 cities in June. According to government officials, the feds were just keeping an eye on the situation.

US Customs and Border Patrol agents flew unmanned aerial vehicles over crowds of Black Lives Matter protesters in at least 15 cities in June. According to government officials, the feds were just keeping an eye on the situation.

Despite the fact these were Predator drones – the same kind the US used to assassinate a foreign general earlier this year – the mission was strictly surveillance. The drones were reportedly unarmed.

Officials say the drones carried no onboard facial recognition software, but nearly 300 hours of film was streamed to ICE agents and other CBP personnel during the operation. Despite it being unconstitutional to film protesters, there’s nothing to stop the government from running this footage through facial recognition software now or in the future. This is normal. You might even say it’s routine.

This is what the Patriot Act, subsequent pro-surveillance legislation by both Democrats and Republicans, and three years of the Trump administration have earned the US. Most citizens don’t think twice about being recorded by the government in public. In fact, many welcome it.

Under normal circumstances, most US citizens don’t have to worry about being caught in the illegal act of simply existing, so the average person shrugs off government surveillance. That hasn’t always been the case.

In June of 1969 it was illegal in every state except Illinois for a person to be queer. This included not just gay, lesbian, and bisexual people, but cross-dressers and drag queens as well. Basically, if the police could catch you dressing or acting queer they could arrest you. Through the use of corrupt, illegal policing tactics including entrapment and wire-tapping, the police “cracked down” on homosexuality throughout the 1950s and 1960s with relatively little oversight and almost no public push-back.

In New York, this proved lucrative for both the NYPD and the Mafia. The cops solicited bribes from affluent or popular queers, often catching them through entrapment. The punishment for these crimes seldom went further than a month in jail and, perhaps, a modest fine. But the real damage came in the form of social banishment.

Police departments made a habit of printing the full names, phone numbers, and addresses of those caught and arrested for homosexuality and other “crimes against nature” in local newspapers and bulletins.

This made it impossible for many of those arrested to resume or begin their professional lives. Not only was being queer illegal, it was also considered a dangerous mental illness. Whether gay, trans, or simply a straight person who enjoyed wearing clothes that challenged social gender constructs, anyone under the queer umbrella was considered a sexual deviant.

In the 1960s and the decades prior, these so-called deviants were subjected to chemical interventions, castration, sterilization, shock therapy, and sometimes even lobotomies. Among the more popular treatments for those deemed homosexuals was aversion therapy. Those accused of being queer would be forced to watch gay pornography while being subjected to violent shocks or other forms of physical harm. The reasoning was that the “offender” would associate homosexuality with pain and discomfort and thus be cured of their queerness.

Most people either didn’t know or didn’t care, and the queer people of yesterday had very few methods of organizing. That began to change in the 1960s as televisions and telephones transitioned from high-end luxury tech to everyday household objects. Much like personal computers and portable music players would later during the 1980s.

With a phone in more homes than ever in 1969, the general population could connect over distance in real-time, for the first time. The world became a lot bigger for marginalized people.

TVs had become mainstream by then as well, and closeted queers would catch a glimpse of freedom on the evening news when reporters talked about places where “homosexuals” congregated. And, thanks to the popularity of government propaganda films in the US, they knew exactly where to find those places.

These propaganda films had a two-fold benefit for the queer community. First, it let queers know they weren’t alone. The government warned that homosexuals were everywhere, they could be anyone! For many queers, this was the first time they realized there were other people out there like them.

The second benefit: these ridiculous films often repeated the names of cities, districts, and neighborhoods where deviants were known to congregate. Rather than scare people away from these queer-zones, crowds of disenfranchised “criminals,” whose only crime was being queer, flocked to places like Greenwich Village in New York.

But being queer was still illegal. So queers moved underground and indoors. Gay bars of the time weren’t fabulous like they are today. They were non-descript places that charged a cover and had to be very selective about who they allowed in. The Stonewall Inn was one of these places.

Today it’s an iconic landmark and a monument to civil rights. In 1969 it was a shit-hole bar run by the Mafia. The booze – most of which was stolen from hijacked trucks – was watered down. The glasses were reused without being washed. And there was no decor to speak of.

But people didn’t go the Stonewall Inn for the ambiance. It was one of the few places where queers could hang out, dance, and have some drinks. Straight people could date, mingle in restaurants, smooch at Lover’s Lane, and hop in the backseat at the drive-in theater. But queers couldn’t so much as hold hands on the sidewalk without risking arrest.

Slow-dancing in a bar with someone you thought was cute must have seemed an enormous privilege to those queers brave enough to risk it in the summer of 1969.

But queers weren’t even safe in gay bars. The Mafia‘s “protection” didn’t extend to the police. In order to keep its doors illegally open, the folks running the Stonewall Inn were forced to pay off cops to avoid raids or having their customers roughed up and arrested as they left the bar.

And even then, the raids didn’t stop. They just slowed and became less aggressive for awhile.

On the night of June 28th 1969, the cops decided to conduct a raid on the Stonewall Inn. Normally, per their payoff arrangement, they’d call ahead to warn the bartenders. But on the night the riots began, they didn’t. They just showed up and began arresting anyone wearing the wrong clothes or standing too close to someone who appeared to share their gender.

Anyone dressed as a woman was sent to an officer who would either grope them or make them expose themselves to confirm their gender expression matched the one the cops thought it should. If it didn’t, they were led out the door to join the other queers being loaded into paddy wagons.

It was business as usual in New York that night. But the police failed to take into account how quickly word of the raid would spread. Thanks to the presence of several nearby payphones, a crowd had assembled outside. The atmosphere was peaceful, perhaps even jovial at that point. Onlookers, many of whom were queers from the Village, just wanted to see what was going on.

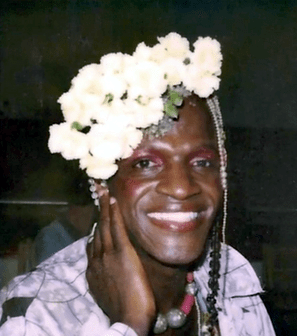

Things changed when a popular drag queen, upon being forced outside, decided she’d had enough. Protesting how the police were handling her, she began resisting. Yet when she and a few others began to fight back, some of them escaping custody, things still didn’t turn violent.

In fact, most eye-witness testimony claims the queens and queers at Stonewall were mocking the police, making fun of them, and even performing Rockette’s-style dance lines as they fought to get free. This wasn’t a clash between warring sides in a battle, it was an episode of the Keystone Cops come to life in New York.

Until it wasn’t.

In one moment, drag queens and queers were leading cops on a wild goose chase through the Village’s streets, ducking into alleys and reorganizing blocks away, essentially making clowns out of their pursuers. In the next, cops still outside the Inn were smashing people in the head with batons and brutalizing people in handcuffs.

By the time day broke, the area surrounding the bar was littered with bricks, stones, and broken glass. And when night descended again, so did the chaos. The Stonewall Riots went on for six nights. What started as a couple dozen people trying to have a good time inside a bar on a Saturday night turned into a revolution featuring hundreds of pissed off queers and queens.

The advent of broadcast television made it possible for all of America to hear about the Stonewall Riots. Though still relatively sparse, media coverage prompted outrage from other minority groups who’d been targeted by police. Worse, for the government in New York, the corruption and Mafia involvement were undeniable and it made city leaders look bad. People in other states started wondering if things like that were happening in their towns.

The riots also inspired other queers to come out and stand up for civil rights. The following year the first “Gay Pride” march happened in New York to directly commemorate the events at Stonewall. And that was televised as well. That was the first time queer people were shown on television out and on their own terms.

Because of the Stonewall uprising and the public’s reaction, the NYPD and, subsequently, law enforcement agencies around the nation changed the way they police. New laws surrounding homosexuality, crimes against nature, entrapment, surveillance, and raids were enacted across the country. It appeared, for decades, that the US would avoid becoming a surveillance state like China or Russia and that queers, Blacks, and women would finally get the rights they deserved. Even the Mafia lost the strength in its grip on marginalized communities in New York as the 1960s gave way to the 1970s.

Unfortunately, changing the laws surrounding queerness, Blackness, or womanhood didn’t solve the problems with bigotry, racism, and misogyny in the US. It just made them social constructs. Queers, non-whites, and women are still second-class citizens in practice if not policy.

The Black Lives Matters protests of 2020 are a clear example of this. Years of smartphone footage, body-cam footage, and other forms of video proof have exposed a corrupt, biased, racist police force that targets and murders Black people. It didn’t happen overnight, but thanks to technology there’s finally some sort of reckoning happening.

The internet, social media, and smart phone cameras are not responsible for the genesis or rise of police and government corruption, just its mainstream exposure. Police brutality didn’t start with George Floyd’s murder in 2020 or at the Stonewall Inn in 1969.

But the problems go deeper than just corrupt cops. This isn’t a matter of bad apples or even a diseased orchard. The whole farm is tainted.

When paramilitary troopers attack peaceful citizens across the country for protesting the murder of Black people it shows how far we are from being the “home of the free.”

Yesterday it was illegal to be queer. Today our First Amendment right to peacefully protest has been taken away. Tomorrow, the US government might decide it’s a crime to be Muslim, or conservative, or a member of the free press. That’s why these riots and protests aren’t about queers or Blacks against cops. They’re about freedom versus oppression. They are a final check against despotism, dictatorship, and fascism.

The Stonewall Riots of 1969 and the Black Lives Matter Protests of 2020 both happened in response to a corrupt system of policing, but they were ignited by technology. The easier it is for marginalized people to connect and unite, the harder it is for government oppressors to control us.

This is why we march. #Pride2020, #BlackLivesMatter

–

Credit: TheNextWeb